When I was infected by hip hop for the first time, I mostly paid attention to the mcs. It was all about Rakim and Kane and KRS ONE. I loved a good beat, but it played second fiddle to a dope verse. It wasn’t until I listened to 3 Feet High and Rising and Enter the Wu Tang for the twentieth time (sometimes I miss the technical limits of the cassette era – being forced to listen to a set of tracks in a defined order on a regular basis really helps you become intimately familiar with every element of each song) that I really noticed how producers like Prince Paul and the RZA weren’t just providing a great track for the mc to ride, but shaping the way listeners experienced the album.

Once I had that revelation, my interest in the producers grew to rival my fascination with the lyricists.

I still believed in the quasi-rockist romantic ideal of the lone charismatic auteur (or collective like the Bomb Squad) expressing their vision through a brilliant hip-hop album. Whenever I played Illmatic, I was interested in seeing the world through Nas’ eyes and experiencing the soundscape created by Large Professor, Q-Tip and the Large Professor. It took another five years for me to appreciate the limits of this perspective. The auteur theory is a great way to analyze style and uncover meaning, but it doesn’t always capture the value of performance or collaboration, especially when it’s applied to music. I didn’t pay enough attention to the engineers, the session musicians and other people involved in the process, and completely overlooked the contributions of the people who played the instruments (whether in the studio or via a sample).

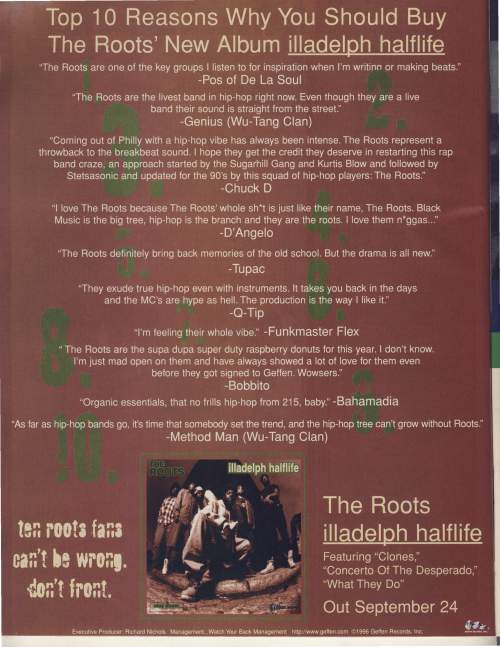

My Record Report-influenced view of the world rendered band members and session musicians who were partially hidden from public view completely invisible until the Roots changed the way that I viewed rap music with Illadelph Halflife vol. 3. In one album, they reminded me that focusing on the identity and intentions of the ‘auteur’ could be a distraction from appreciating the music.

The Roots are different from most hip-hop groups. Some of that is related to their musical choices. They are a band that (mostly) specializes in a genre that is typically performed by mcs and djs. They are one of the few hip-hop groups that specializes in earnest cross-genre cover songs. The Fugees had a similar reputation early in their lifespan, but they rarely strayed from reggae and r&b from the seventies. The Roots will play anything. They are more rugged than most of their ‘conscious’ contemporaries, but they never seemed desperate to be seen as ‘cool’ or feared appearing nerdy. They never give you the album you expect. When we expected a jazz influenced album in 1996, we received a stripped down album inspired by boom bap hip-hop. Over the next 19 years, the Roots did live albums, pioneered a uniquely hip-hop flavored take on neo-soul, experimented with different genres and concept albums and released album length collaborations with both expected (John Legend) and unexpected (Elvis Costello) artists. A number of other artists who emerged from the overlapping underground, ‘conscious’ and fusion scenes in the early nineties shared similar qualities, but the Roots were the only ones who took great pains to remind everyone that they were a band. The musicians that were typically unseen were on the album covers and name checked in profiles. We saw the guy who played the bass and the dude played the keyboards. Hell, the most talkative and charismatic one wasn’t the mc, but the drummer.

The mere existence of the Roots as a hip-hop band should have been enough to change the way I thought about hip-hop, but I didn’t pay much attention to them before Illadelph Halflife. I was first exposed to the Roots in early 95, a little bit after the band released Do You Want More?!!!??! It turned out to be one of the best albums of the year, but when I first heard it, I couldn’t avoid comparing it to the albums released in 1994. Do You Want More?!!!??! was entertaining, but in a year with Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, Creepin’ On Ah Come Up, the Blowout Comb, On the Outside Looking In and Stress: The Extinction Agenda (and those are just the group albums!), it felt like a minor work, an advertisement for their already-legendary live shows.

The Roots were clearly talented, but just didn’t do enough to stand out in a year filled with groundbreaking hip-hop music. One year later, the Roots released a perfect hip-hop album. They found the perfect balance between showcasing their virtuosity and creating music that felt moving and meaningful.

Black Thought is the lead vocalist for the Roots, but he is not its frontman. He’s not the one with the clever quotes in magazine profiles or the one who clearly articulates a vision for the band’s albums. Even when he blacks out on a track, it feels more like a drum solo than an assertion of dominance. I’ve always thought that was one of the reasons why Black Thought’s name rarely comes up in top ten lists. He doesn’t project the kind of ego or arrogance that we associate with great mcs. He lets his talent speak for itself. Some mcs of the era made their case for GOAT through legendary magazine profiles and radio interviews. Others made their case by proclaiming themselves the king of their region or calling themselves the GOAT in their verses. Black Thought just records amazing songs. Black Thought hits the ground running on his opening statement, Respond/React.

It’s just hip hop and you know my head heavy, Malik said ‘Riq, you know the planet ain’t ready for the half and we coming with the action packed on some Dundee shit representing the outback

The transcription doesn’t do it justice. Thought’s combination of gentle (almost whispered) delivery with hard hitting abstract lyrics pulls the listener in, and you feel the song start to build momentum even before the aggressive chorus. Respond/React evokes the hip-hop cipher that exists in our collective imagination, where freestyles aren’t derivative or boring and rappers are accompanied by amazing drumming and keyboard playing (and of course, a harp).

Black Thought goes on to dominate the album for almost eighty minutes with Malik B as his Russell Westbrook. It’s the kind of performance that hip-hop fans like me tend to compare to an athletic performance, if only because you experience a similar involuntary response, the sharp intake of breath that follows an amazing pass or a thrilling shot. He does the abstract battle-rap ‘lyrical exercise’ stuff that was typical of the time, but also shares trenchant social commentary, tales of lost love and insights about the state of black America and hip-hop in 1996. The three tracks that don’t feature his vocals feel like a necessary breather from the lyrical onslaught. It’s impressive, but what distinguishes Black Thought from other mcs of the era isn’t his sheer virtuosity (there were plenty of hyper-talented mcs at the time), but his (and the band’s) generosity of spirit, as demonstrated through his collaborations.

This was a time when every hip-hop album featured a guest verse from a crew member, label mate, hungry up and comer or established veteran. Most guest artists were limited to a single verse and were walled off from the main artist by the chorus. On very rare occasions, the guest would trade 4-8 bar verses with the main artist between choruses (e.g. Jay-Z and Notorious BIG on Brooklyn’s Finest) or lines with the main artist in the third verse (e.g. Kool G. Rap and Nas on Fast Life), but the best you could typically expect was a quick sixteen bars from the guest artist. I rarely got the sense that the two artists were working together to develop a song. Most of the time, it sounded like the guest verse was crudely affixed to a nearly-completed product. I imagine that there were a lot of practical reasons why this was the standard practice in hip-hop, but one may be that the spirit of competition that we associate with rapping inhibits real collaboration. If you’re focused on having the strongest verse, you might not be thinking about how to make the best song. As a result, even the best guest appearances on hip hop albums felt somewhat inorganic. On Illadelph, the guest spots from non-crew rappers like Common and Q-Tip feel like real collaborations, giving the album an improvisational vibe that is extremely rare in hip-hop studio albums. The band plays to the strength of each guest – a fluid collaborative song for Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest, a loose, an ethereal neo-soul song for D’angelo, a boom bap track for Common, and a smooth jazz track for Cassandra Wilson. The guest spots feel like featured appearances (especially by non-vocalists) in other genres, where collaboration is more important than competition.

On Ital (The Universal Side), Q-Tip and Black Thought trade vocals with an ease and dexterity that you might expect from veteran hip hop duos. On the first verse, the two exchange bars at a rapid clip, with the space between their lines shrinking until their vocals overlap.

BT:

You know the Bad Lieutenant be on some whole ‘nother other finesse genetic

They say I get it from my mother so it’s inherited/ary and very necessary to shine legendarily/heavily refined/contemporary…

QT:

Contemporaries like the Roots is so rad,

it’s like dag, which bag did they come out of?

And how can I get in it and win it

Like a raffle ticket picking, if you feel like you stuck, then guess who did the sticking

The listener is breathless by the time the chorus hits. The second verse is even better. The mcs divide it in half, with Black Thought’s words (“it’s a wonder they alive…) seamlessly blending into Q-Tip’s lines (“and still breathing”). Ital captures the confluence of their two distinct approaches to hip-hop – you find yourself hypnotized by Q-Tip’s idiosyncratic flow and mesmerized by Thought’s impressive wordplay (it’s not just the brilliant metaphors, but the way he manipulates language).

Although Thought cements his position as one of the best mcs in the world on Illadelph Halflife, the listener is never allowed to forget that Illadelph Halflife is an album by the Roots, not Black Thought ft. the Roots. If you are a traditionalist, you would be forgiven for thinking that Black Thought is the focal point on the album, but each member of the band feels critically important. On a number of songs, it’s not hard to think of Thought’s voice as just another instrument. Although much of the album’s production is credited to Grand Negaz (the collective title for Questlove, Black Thought, Anthony Tidd, Mel “Chaos” Lewis, James Poyser, Kelo and Richard Nichols) or some other combination of band members, the role that each musician plays in creating the music is incredibly clear. On Panic!!!!, you are transported by Black Thought’s hard-hitting vocals, but the song works because of the interplay between Thought’s vocals, Rahzel’s beatboxing and ?uestlove’s drumming/keyboard playing/tambourine shaking.

Illadelph remains one of the few perfect albums in a year crowded with classic hip-hop albums, from ATLiens and The Score to All Eyez on Me and Reasonable Doubt.

This view is complicated a bit by ?uestlove’s perspective. In a number of interviews, he has described Illadelph as the group’s attempt to give the industry and the marketplace what it wanted – “a ‘real’ hip hop album, you know, the ‘hard Wu-Tang stuff’”. Where Do You Want More?!?! sounded like a preview of the Roots’ live shows, Illadelph felt like a polished, pristinely (almost obsessively) produced artistic statement, a (self) conscious effort to produce a ‘hip hop album’. The band incorporated more record scratches, beatboxing and guest appearances from simpatico rappers, while Questlove did his best impression of a drum machine. Black Thought’s vocals became more structured and less abstract. No more scatting (Datskat) or repeated verses (Lazy Afternoon). They even started sampling (their old jam sessions), although I’d be lying to you if I told you that I know where the live instrumentation stops and the sampling begins. From the perspective of it’s primary architect, it’s auteur, Illadelph was intended to be a commercial compromise to appeal to a larger audience. Does this make Illadelph a sell-out move (or less perfect)? Of course not.

When I was a teenager, I wanted to believe that my favorite albums were made to satisfy the personal creative muses of the artists and producers. I embraced the ‘artists always valiantly resist the demands of the suits and the expectations of the marketplace’ narrative. When I first heard Illadelph, I imagined that the Roots were simply interested in sharing their take on hip-hop culture and exploring different elements of the genre.  I thought that this made them better than artists who put out formulaic music that ‘pandered’ to a specific market (whether defined by age, region or gender), the ones who made sure that every album featured a posse cut, a ‘bitches ain’t shit’ track and ‘one for the ladies’. The Roots may have been less openly formulaic, but in some sense, an album like Illadelph was just as much of a product as an album like No Way Out. I didn’t want to admit that, because it would that would mean that the music was more important than the narratives we build around the music. I was way too committed to hip-hop kayfabe in high school. I was also far too committed to the notion that the vision or opinions of an album’s ‘auteur’ was more valuable than the opinions of others. As it turns out, I was wrong about a lot of things when I was in high school.

I thought that this made them better than artists who put out formulaic music that ‘pandered’ to a specific market (whether defined by age, region or gender), the ones who made sure that every album featured a posse cut, a ‘bitches ain’t shit’ track and ‘one for the ladies’. The Roots may have been less openly formulaic, but in some sense, an album like Illadelph was just as much of a product as an album like No Way Out. I didn’t want to admit that, because it would that would mean that the music was more important than the narratives we build around the music. I was way too committed to hip-hop kayfabe in high school. I was also far too committed to the notion that the vision or opinions of an album’s ‘auteur’ was more valuable than the opinions of others. As it turns out, I was wrong about a lot of things when I was in high school.

Illadelph sounded more like the kind of classic ‘boom bap’ New York hip hop albums from the early ‘90’s than Do You Want More?!?, but it would never be mistaken for a Premier or Rock album. It’s not just because the album includes proto-neo-soul songs like One Shine or ends with a brilliant (and long) spoken word performance from Ursula Rucker. It’s that even their most traditional songs draw the listener’s attention to the contributions of individual artists more than most hip-hop of the era. A sample heavy song like Concerto of the Desperado sounds like they were created by a producer instead of a band, but I’m still drawn to Amel Larrieux’s ethereal background vocals. Kelo (the producer of the track) does a great RZA impression, but I’m not sure that I would’ve noticed Larrieux as much if RZA had produced this track. Questlove may have intended for Illadelph to serve as a sop to the mainstream fans, but for me, the album’s a reminder that the line between alternative and mainstream hip hop is blurry and easily crossed. It taught me that artists can incorporate other musical genres, traditions and approaches while staying true to hip hop (and competing with more traditional acts on their own terms).

In a year when about half of my conversations were about hip hop top ten lists, the Roots’ approach to music reminded me that the GOAT approach to evaluating hip hop was ridiculous and shattered my preconceived notions about the genre. An mc could blow your mind without being a star. An album that’s designed to pander to a traditional hip-hop audience could excite those hungry for something different. And every single musician and artist who work on a song or album matters.

In a year when about half of my conversations were about hip hop top ten lists, the Roots’ approach to music reminded me that the GOAT approach to evaluating hip hop was ridiculous and shattered my preconceived notions about the genre. An mc could blow your mind without being a star. An album that’s designed to pander to a traditional hip-hop audience could excite those hungry for something different. And every single musician and artist who work on a song or album matters.

Illadelph Halflife Vol. 3 exploded my ideas about hip hop. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the album helped me understand that hip hop is a collaborative art and appreciate the individual contributions of everyone in the process.

Soundtrack (click through for the full playlist)